Written by Sidharth Chatrath & Gitanjali Diwakar

OP Jindal Global University

Final year law students

February 2025

Introduction

Over the years, the Courts[1] and various committees have highlighted the unique aspects of India’s police hierarchy. Voluminous reports have noted the vast range of duties bestowed upon these personnel (i.e. from recording complaints to providing expert testimonies and more). The lack of uniformity in the system, however, raises questions of its administrative effectiveness. This article, thus, delves into these elements by analysing the police administration of two states – Kerala and West Bengal.

Dissecting accountability

Paul H. Appleby opined that hierarchy is a means by which resources are apportioned, personnel selected and assigned, operations activated, reviewed and modified.[2] India’s police services demonstrate the application of this principle. However, owing to its unique stature guaranteed by the Constitution, they do not adhere to a uniform ranking or administrative system. This creates variations in the sphere of accountability. The following examples depict these elements.

Chalking out police hierarchy: Kerala v West Bengal

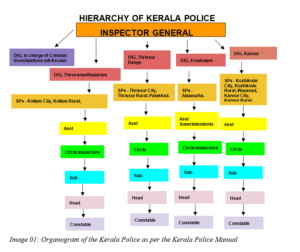

As per the diagram (Image 01), all districts, except for Ernakulam and Thiruvananthapuram, involve Superintendents and their subordinates in the administration process. More importantly, crime in the State is monitored by a specific official i.e. The DIG in-charge of Criminal Investigations.

Image 01: Organogram of the Kerala Police as per the Kerala Police Manual

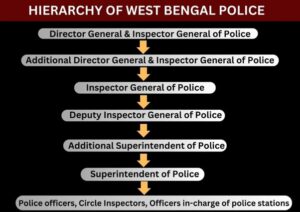

The structure varies to a certain extent in the case of West Bengal, where the police administration is divided into eight ranges and three zones. It involves:

- a) 10 Director Generals and Inspector Generals of Police (DGP & IGP)

- b) 27 Additional DGP & IGP

- c) 35 IGP

- d) 22 Deputy IGPs

- e) 106 Superintendents of Police

- f) 53 Additional Superintendents of Police

- g) Six Police Commissionerates

An Additional DGP or Additional IGP heads each region while the ranges are administered by an Inspector General or a Deputy Inspector General of Police. An Inspector General or a Deputy IGP heads the Commissionerates. The Superintendents manage the police stations and the other police forces in the districts. The Commissionerate oversees the police forces in its entirety.

These differences often lead to lapses in their primary role, i.e. maintaining order within the state. This negatively impacts credible investigations, systematic documentation of reports, and more. The cases of doctors’ deaths in Kerala and Kolkata have highlighted some of these aspects.

Vandana Das case: Alleged police inaction

The death of a doctor in Kerala in 2023 spearheaded many discussions surrounding police accountability. Reports of the case highlight that the victim succumbed to the injuries after being stabbed several times with a pair of scissors by the accused. The dismissal of the petition herein does not nullify the significant eyewitness accounts.[3]

The inaction by the police personnel present was acknowledged by the Kerala High Court.[4] To begin with, the Assistant Sub-Inspector, the Home Guard, and the police driver, did not remain at the scene of the incident after being subject to an attack by the accused. But the absence of strong evidence to prove this facet absolved them from this faulty behaviour. Also, the Kerala High Court chose to steer away from the law of the land as established in a catena of judgments following similar investigations in the past. The reason for their decision was the absence of ‘criminal intent’ by the police.

2024 RG Kar case: Gaps in police duties

The recent death of a second-year medical student at Kolkata’s RG Kar Medical College depicted the impact of inefficient police work.[5] Investigations herein were assigned to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) after the Apex Court acknowledged the ambiguities in the procedures followed by the Kolkata police. These included incorrect information about the time of the victim’s death, and the discrepancies in the police diary. The authorities had delayed the registration of the complaint by five days too.[6] The police also did not record the relevant statements related to the crime as mandated under Section 180 of the BNSS. While the accused in this case has been arrested, the progress report demonstrates how justice is at stake when the police tamper with crucial evidence.

Police reforms: Past recommendations on investigations and accountability

Central and State laws govern India’s police services. The Constitution of India has designated “police” as well as “public order” under the State List.[7] But this does not relieve the states from the Centre’s interference in the police’s activities. Certain aspects such as training police officers,[8] and extending their powers beyond a state’s boundaries[9] are subject to the Union Government’s authorisation.

The total number of laws implemented in this regard remains undetermined. The oldest of them is the Police Act, 1861. Since then, each province/state has established statutes on these lines, implying varied implementation mechanisms too. The lack of cohesion among these legislations as well as the rules associated with them were noted by the Apex Court in Prakash Singh vs Union of India[10]. Most importantly, the citizens’ shaky trust towards such personnel also causes issues in such a system.

Past recommendations for reforms: A summary

India’s criminal justice system has been criticised over the years. Despite numerous discussions surrounding reforms, its implementation remains largely draconian. A glimpse of the recommendations by various authorities showcases the gaps in the police administration. Interestingly, police accountability remains a constant in these reports.

Highlights: 2nd Report of the National Police Commission- August 1979[11]

- Criminal Justice Commission

1.1 Setting up a Criminal Justice Commission to comprehensively reform all agencies of law enforcement with corrective measures.

Highlights: 5th Report of the National Police Commission- November 1980[12]

- Police conduct

3.2. Police officers should develop an attitude of courtesy and consideration towards members of the public who come to them for help.

- Victims of crime

4.1. The criminal justice system shows no concern for victims of crime. A Criminal Injuries Compensation Act should be drafted.

Highlights: 8th National Police Commission Report- May 1981[13]

- Accountability for performance

1.1. There should be continuous monitoring of the performance of each police force. The State Security Commission should have an independent cell to evaluate police performance.

1.2. The State Security Commission will prepare a report on the police’s performance in its state for the state legislature. This report will be informed by the Chief of Police’s annual administration report and the Central Police Committee’s assessment report.

1.3. Police officers should be taught the concept of accountability to the people, both as individuals and as an organisation.

Highlights: Padmanabhaiah Committee (2000)[14]

- Police performance

7.1. A permanent National Commission for Policing Standards should be established to lay down common standards for the police across the different states, and to ensure state governments set up mechanisms to enforce the standards.

7.2. An independent Inspectorate of Police should be set up in law to monitor the police organisation and to provide reports to the state government on police functioning. The Inspectorate should provide annual and thematic reports.

- Police accountability

8.3.If a complaint is made of rape of a woman or death of any person in custody, a judicial enquiry should be mandatory.

Highlights: Police Act Drafting Committee (2005-2006)[15]

- Control and supervision of the police

1.1.Superintendence of the police shall vest in the relevant state government. The state government must be responsible and ensure an efficient, effective, responsive and accountable police service.

- Accountability for performance

11.2 Identified performance indicators must be used along with the plans to evaluate organisational performance. The Police Board must identify these performance indicators, which should include:

- operational efficiency;

- public satisfaction;

- victim satisfaction (both in terms of police investigation and response);

- accountability;

- use of resources; and

- human rights record

- Accountability for misconduct

12.1. Police misconduct that affects the rights of the public must be addressed internally or externally (external review should be undertaken by independent civilian accountability agencies at the state and district levels) depending on the gravity of the offences. Police misconduct that violates prescribed codes of behaviour without affecting an individual shall be dealt with internally through departmental procedures that award appropriate penalties.

Conclusion

“The true measure of a police officer’s success is not in the number of arrests but in the trust and safety felt by the community,” said Kiran Bedi, India’s first woman IPS officer and former Lt. Governor of Puducherry. Citizens are entitled to a safe existence. It is therefore essential to analyse the reasons behind the ineffective implementation of various expert recommendations in this concern.

The principles surrounding the delegation of powers as laid down by Justice Fazl Ali are pertinent at this juncture.[16] The police must also uphold the doctrine of natural justice.[17] They must not infringe a citizen’s rights whilst exercising their powers. Adequate checks and balances should be of paramount consideration in the conduct of police personnel. Efforts must be made to establish a certain degree of uniformity in the current mechanism.

Hence, a re-look at the police administration would help set the stage for a robust and reliable criminal justice system. The members of the police fraternity must advocate for a change in approach and execution of procedures. It would be a step towards rekindling the citizens’ trust in the laws of the land. In the words of Rajeev Dasot, IPS – “Progress is impossible without change, and those who cannot change their minds cannot change anything.”

[1] Prakash Singh vs Union of India, (2006) 8 SCC 1.

[2] Romme, A.G.L., Climbing up and down the hierarchy of accountability: implications for organization design, Journal of Organisation Design, (2019).

[3]KG Mohandas & Ors v CBI & Ors, (2024), KER, 8372.

[4]Supra note 4.

[5]In Re: Alleged Rape and Murder Incident of a Trainee Doctor in R.G. Kar Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata and Related Issues, (2024) SC 2488

[6] XXXXX (Parents of Victim) v The State of West Bengal & Ors. WPA(P) 339 of 2024, accessed on September 24, 2024.

[7] Seventh Schedule, Constitution of India.

[8] Section 65(a), Seventh Schedule, Constitution of India.

[9] Section 80, Seventh Schedule, Constitution of India.

[10] Prakash Singh vs Union of India, (2006) 8 SCC 1

[11] Swati Mehta, Navaz Kotwal and Fahad Ahmad, Police Reform Debates in India (Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative)

[12] ibid.

[13] Supra note 12.

[14] Supra note 12.

[15] Supra note 12.

[16] In Re: The Delhi Laws Act, 1912, AIR 1951, SC 332.

[17] Harla v The State of Rajasthan, 1951, AIR 467.